Roger Zelazny’s biographer and friend, Ted Krulik, is sharing insights and anecdotes from the author.

In his introduction to Roger Zelazny’s story collection Four for Tomorrow, Theodore Sturgeon called Roger a “prose-poet” whose stories created “memorable characters, living ones who change, as all living things change, not only during the reading but in the memory as the reader himself lives and changes and becomes capable of bringing more of himself to that which the writer has brought him.” (“Introduction,” Four for Tomorrow, New York: Ace Books, p. 7, 1967).

Sturgeon’s assertion can be exampled by two protagonists from stories in Four for Tomorrow: Gallinger in “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” and Carlton Davits in “The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth.” Roger meant for these stories to memorialize the space adventures of the pulps, but these tales were also Roger’s training ground for developing his unique signature style. Typically, a Zelazny protagonist is extremely talented but is also personally flawed in his relationships. How this character experiences things can be just as important as the science fiction milieu of the story.

Space Opera

When Roger wrote “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” and “The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth,” he was paying homage to the space operas he had read in his youth. But he infused the genre with his version of a protagonist who, while brilliant, was somehow incomplete.

Roger wanted Gallinger to reach emotional maturity on the old Mars that Burroughs envisioned; he wanted Davits to discover his self-respect on the oceans of Venus. In our 1982 interview, Roger discussed the urgency he felt in telling these stories at the time that he did:

I happened to like the name Gallagher and I decided on a variation of it for the story “A Rose for Ecclesiastes.” The name Gallinger seemed euphonious. I wrote “Ecclesiastes” in the fall of 1961 and submitted it in the summer of ’62.

The story is a comment on the genre of space opera but I didn’t intend it as satire. It was a piece of nostalgia for me. Space opera was the sort of story on which I grew up. When I was younger, I read heavily in pulp magazines. They were readily available in the stores. I had a sentimental feeling for that kind of story and I had to do it then because our knowledge of the solar system had changed so rapidly. It was becoming apparent that the Mars described by Edgar Rice Burroughs or Leigh Brackett or Edmond Hamilton—that Mars, or that Venus—the great watery world—that these simply did not exist.

By late 1961 we already had fly-by photos which indicated what the surface of Mars and Venus were really like. But the knowledge was not yet so disseminated to the public, and so one could still get away with a story of the older variety. I realized that I was at the last point in time when I could write that sort of story.

So I wrote “A Rose for Ecclesiastes” set on the old-fashioned Mars with red deserts and breatheable atmosphere. The story was a composite of all my feelings of the old Mars. And I resolved to do a story about the old Venus very quickly afterward, “The Doors of His Face, The Lamps of His Mouth.” That was it. I could never do another story of that sort again. They were both my tribute to a phase in the genre’s history which was closed forever.

—Santa Fe, NM, 1982

Interstellar Relations

Roger pursued the science fiction themes of interstellar space travel, relations with extraterrestrials, and the discovery of alien cultures in several novels and short stories throughout the 1960s and 70s.

When Roger answered my questions about the novel To Die in Italbar, he told me of a writing technique he had taken from a renowned author of a different genre of fiction: The Early American West. Roger explained it this way:

I had to write To Die in Italbar in a hurry and I figured I needed some sort of formula to guide me. I decided to try one that novelist Max Brand claimed he used. He said that he always started with a good guy who went bad and a bad guy who went good, and then had them cross over on their way to down-and-out. Since he had written about three hundred books, I felt he must have known what he was talking about.

In my novel, I see Malacar Miles as my bad guy on a collision course with Heidel von Hymack, or Mr. H. Mr. H is on a life-saving mission and Malacar wants to use H’s unique ability to enable him to destroy the prevailing establishment.

Both Malacar and Mr. H are idealists but they come from opposite poles. These characters have ideals that become twisted because they have been disillusioned—Mr. H, because his healing can turn to death-causing; and Malacar, because of his hatred of the government that dominates his realm.

Malacar had been a rebel holdout against the interstellar government, believing in his cause to the extent that he resorted to arson, bombings, and murder. He is in process of changing because of Shind, an alien who communicates with him telepathically. The alien friend represents that part of humanity that Malacar had resigned when he became whatever he was. Malacar had given up on the softer feelings that Shind still felt and shared with him.

Mr. H has a special physical condition that allows him to eradicate disease when in proximity to others but when he remains too long in one place causes virulent disease that leads to death. He comes to Italbar to cure a sick child but when he stays too long people in contact with him die horrible deaths. His change occurs when he is branded an outlaw in the city and hunted out.

Just as some people say Satanism is just an inverted form of Roman Catholicism, H and Malacar’s ideals were once pure and noble and so forth—but when they became disillusioned by it, they went the other way and became destroyers.

—Santa Fe, NM, 1982

The Human-Machine Interface

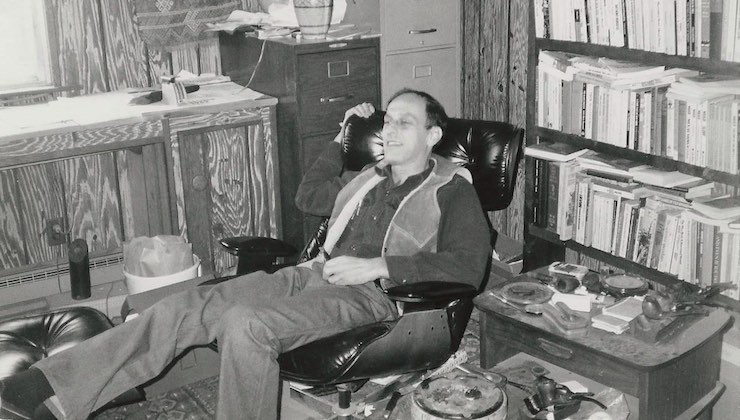

Roger didn’t use a computer. “I don’t have any computers in my house,” he told me in 1985. “I still have a typewriter in my lap and an easy chair.” Of course, computers weren’t as ubiquitous in the ‘80s as they are today, but it may nevertheless seem surprising to younger readers that Roger hadn’t used one. In our talks, Roger revealed that he did have some knowledge of computers. “I know an awful lot about computers on a theoretical level. I’ve been following computer development for years.”

Roger was fascinated by the new technologies that were leading to the mechanization of humans. In a number of stories, he explored the theme of cybernetics. He was most interested in writing about the consequences of integrating man with machine. For Roger, the consequences of such an advance in our technology supplanted the clichéd idea of a robot servant in human form. In fact, he felt that the theme of robots in fiction was a bit old-fashioned. He made the following explanation:

Robots are very tricky to design and expensive whereas humans are cheaply manufactured. Humans can handle things with greater manual dexterity than most robots I’ve known.

We’re in a more information-processing period now. The old concept of the robot as a humanoid man-servant is pretty much passé. When one thinks of robotics these days one tends to think of mechanized assembly lines.

I’m more interested in the human-machine interface. The development of various prostheses interests me in questions such as where the human ends and the machine begins. I have often thought of doing a story with someone either as a human being or as a robot who, by a series of stages, changes into the other end of the spectrum. By the story’s end, he’d be either totally robotic or totally human, the opposite of what he once was. And possibly . . . bring him back again.

I could see myself writing a story about two characters coming from opposite directions; a robot that becomes human and a human who becomes a robot. I could have them pass each other along the way toward becoming metal or flesh. It would be a variation of Old West writer Max Brand’s plotting notion about two characters: a good guy and a bad guy. The plot has the bad guy turn good and the good guy go bad, and then have the two pass each other along the way.

From a structured standpoint, it might be fun to write a story with something like a jukebox which becomes human and, maybe, a pop singer seeking to become mechanized.

Yes, I see that as a very interesting idea to explore.

—Lunacon, Tarrytown, NY, 1989

The Discovery of What Happened and Why

In 2009, fans were delighted to learn that a previously unpublished Zelazny novel, believed to have been written around 1970, had been discovered. Roger’s son Trent arranged to have Dorchester Publishing put it into print under the title The Dead Man’s Brother. Dorchester marketed it under its “Hard Case Crime” imprint. That’s right. It was a mystery novel. It’s plotting was reminiscent of a Sam Spade story but the witty colloquial dialogue and cultured style bore Roger’s stamp.

Roger’s interest in combining the science fiction and mystery genres can be clearly seen in the three novellas collected in My Name Is Legion. The novellas, about a nameless protagonist who solves mysteries grounded in technology, were entitled “The Eve of RUMOKO,” “Kjwalll’kje’koothai’lll’kje’k,” and “Home Is the Hangman.” “Home Is the Hangman” won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards in 1976.

Roger liked his Nameless Character, especially because he had found a way to escape a near-future society that had digitized every aspect of people’s lives on computer. Remember: Roger wrote these tales in the 1970s. The Nameless Character lived outside the confines of society, playing the roles of secret agent and detective with glib skillfulness. Roger described why he enjoyed combining the two genres and telling the story of this protagonist so much:

So long as no one knows everything about you, you have resources you can call upon for which no one is really prepared. That’s what fascinated me in my Nameless Character in the My Name Is Legion stories. He has escaped the system, what I call “The Big Machine.” It seems to me, once The Big Machine, or anyone else, knows everything there is to know about you, you become that much more predictable; therefore, that much more controllable.

I’m thinking of doing a complete novel with the Nameless Character from the My Name Is Legion series. Perhaps do some more novellas if I can find the right idea to work with.

I happen to know a retired CIA field agent. He’s the last person on earth you’d believe worked for the CIA. If I was walking through a crowd and had to identify what he does, I would have guessed a retired insurance salesman or car dealer. Something like that. He was a completely ordinary-looking person. He was anonymous. Whenever I think of a person who has a dangerous occupation, I imagine a certain amount of anonymity is required.

The Nameless Character calls himself by any number of obviously phony names: Albert Schweitzer, James Madison, Stephen Foster. Other characters who meet him simply accept them. In a way, he’s knocking the system. He can take the most improbable name and, if it’s on paper, and The Big Machine says that’s his name, everyone accepts it at face value.

I consider the Nameless Character one of my hard science characters. He’s into geophysics in one novella, dolphins in another, and artificial intelligence in the third. He’s a special character in that he has to function in a mystery where the crux of it is some scientific idea. Yeah, I like him. I don’t think I’ve finished with him yet. It could be years, or perhaps sooner, before I get back to him, but I’m not done with him.

I like combining mystery with science fiction. There is something about the mystery form that appeals to me. As a writer, I like setting up the location of clues and the discovery of what happened and why. And I enjoy creating the final confrontation scene where everything is explained and the final action takes place. I’ll do something like that again, too.

—Santa Fe, NM, 1982

Theodore Krulik’s encyclopedia of Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, The Complete Amber Sourcebook, published in 1996 by Avon Books, is still the most exhaustive reference book on that revered series. Through his literary biography Roger Zelazny, published by Frederick Ungar Inc. in 1986, Krulik made accessible to the enthusiast the famed author’s personal concerns. For the first time, aficionados discovered the sources in Zelazny’s own life that inspired his writing. Other literary work includes essays on Richard Matheson in Critical Encounters II for Ungar, edited by Tom Staicar, and on James Gunn’s The Immortals in Death and the Serpent for Greenwood Press, edited by Carl Yoke and Donald Hassler. As a member of the Science Fiction Research Association, Krulik wrote a regular column for their newsletter in the 1980s and 90s entitled “The Shape of Films To Come.” Currently, he is writing a novel about a science fiction writer who gains remarkable powers to see into the minds of others. Krulik hopes to complete World Shaper by the end of 2017.

Theodore Krulik’s encyclopedia of Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, The Complete Amber Sourcebook, published in 1996 by Avon Books, is still the most exhaustive reference book on that revered series. Through his literary biography Roger Zelazny, published by Frederick Ungar Inc. in 1986, Krulik made accessible to the enthusiast the famed author’s personal concerns. For the first time, aficionados discovered the sources in Zelazny’s own life that inspired his writing. Other literary work includes essays on Richard Matheson in Critical Encounters II for Ungar, edited by Tom Staicar, and on James Gunn’s The Immortals in Death and the Serpent for Greenwood Press, edited by Carl Yoke and Donald Hassler. As a member of the Science Fiction Research Association, Krulik wrote a regular column for their newsletter in the 1980s and 90s entitled “The Shape of Films To Come.” Currently, he is writing a novel about a science fiction writer who gains remarkable powers to see into the minds of others. Krulik hopes to complete World Shaper by the end of 2017.